When you come from a family of the ultimate not-haves, just how cool is it to be able to hold up a book and say: “This has been written about us.”?

And a good book at that?

Well, you can take it from me: it is cool. Precious, in fact. So much so that I wanted to make sure to pass this book on to my children.

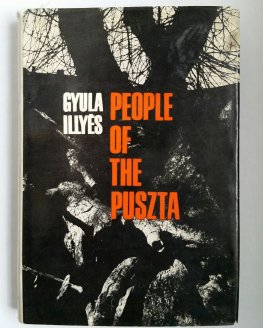

Gyula Illyés

Gyula Illyés came from a piss-poor family in a puszta in the middle of Transdanubia, within a few kilometres of where my family comes from. By talent and hard work, he somehow managed to rise from the world of the puszta to become a famous writer and intellectual. He was only a few years older than my great-grandfather – who too was from a piss-poor family. The childhood Illyés describes was still pretty much the childhood my grandmother had; she remembered some of the events described in the book. I myself spent the long summer vacations of my childhood right there where many of these events happened; my grandparents, aunts and uncles speak with the same accent Illyés did. I used to drop into the same accent within days of arriving to my grandma’s house, every time.

The Puszta & its People

To understand where Illyés and my family come from, you have to understand the concept of the puszta as it then was in Transdanubia, Western-Hungary, because generally in Hungarian and in the world this word is better known to mean big sweeping plains (like the steppes of Russia, say). A Transdanubian puszta on the other hand was a kind of a hamlet (if you can call the handful of buildings a hamlet) on the big farm estate.

In the beginning of the 20th century, when this book is set, most land in Transdanubia was held by a few big families who hardly ever even went near their estates but employed a farm manager or agent, who then managed the work force. This work force was invariably composed of the landless peasantry of which there was ample supply (despite of high rates of emigration to America). The peasants were hired as day labourers and if they managed to get a more permanent position, such as a coachman or a wheelwright, they were given some huts to live in right there on the puszta. Their life was very much like the life of a medieaval serf; their prospects to better themselves practically non-existent.

My great-grandfather was one of the lucky people: he had a permanent position. Moreover, he was employed as a coachman by the local landowner at a time when he couldn’t get any other work. He had come back from a Russian POW camp in the aftermath of World War I and as such he was ‘tainted’ by communist ideas and nobody would employ him. Thankfully the local land manager knew the family well and was not worried that my great-grandfather would want to start a communist agitation on the estate! (Nor did he.)

The people, my family included, lived in low single story houses which consisted of two rooms and a kitchen. These were strung out in a row:

room 1 – shared kitchen – room 2

Each family had a room to themselves, that sometimes meant twenty people in the same room: several generations. The families decorated their room as best as they could which was nothing much. They were often short of having enough furniture even. The floor was a dirt floor, ie. just the ground trampled solidly underfoot. This was the same in the kitchen which was shared with the neighbouring family. Each family had its side of the kitchen, so to speak, where they kept their pots and pans and their meagre supplies – having to borrow a spoonful of sugar or a few potatoes from the fellow kitchen user or the neighbours in the next building was common. No bathrooms of course; outhouses were built instead well away from the living spaces.

… I can remember only the house with its two tiny rooms adn the earth-floored kitchen in between. The yard stretched as far as the eye could see. When I first struggled over the well-worn threshold, the infinite world lay at my faltering feet. The house stood on a hill. Beneath it in the valley lay the puszta, which conformed to the usual pattern. To the right lived the steward, the farm foreman, the mason and the wheelwright; in the same block of buildings were the forge and the wheel-shop. To the left were three or four rows of long farm servants’ quarters, then there ws the manor-house among its age old trees, the the famr manager’s dwelling. Immediately opposite was a large cart-shed in Empire style, behind which on a little rise stood the granary and the ox-stables. All around lay the endless fields, speckled with the white smudges of distant villages.

The puszta families lived in a sort of timelessness. It’s not that area had no history (it has plenty and varied, all the way back to the Romans) but they themselves, being uneducated knew nothing much about it. Their life was ordained by the seasons.

It was something of a disgrace to be a puszta-dweller; it implied having no roots, no native land and no fixed above – which of course is true.

…If you want to know where a puszta-dweller comes from, you do not ask him where he lives or even less where he was born, but who his master is. My own family served mostly the Apponyis, then the Zichys, Wurms, Strassers and Königs and their relations – for the landed gentry were apt to exchange their servants for with their relatives: thus a clever cowman, a good-looking coachman or a deft-fingered gelder would be transferred or even presented to one of the relations, this being regarded by the servants themselves as a mark of special disctinction.

The lives of the families were mostly directed by the local landowner or his agent: it mattered little which puszta a child was born since the administrative arrangements kept changing (ie. which nearby village the puszta happened to be belonging) and the families could be uprooted from one day to another and transferred to another estate owned by the same land owner.

So we wandered from place to place, sometimes taking all our odds and ends, our collapsible hen-houses, our hens and the cow; sometimes it was only to visit relatives, a brother or sister-in-law who had suddenly been snatched away after living nearby for five or six years. Sometimes we drove all night and all morning in the wagon, but we were never away from a puszta, and felt at home everywhere. The house were I was born did not belong to my father, bu in the land of my birth, I received an unrivalled inheritance. I can call half a county my own.

The Gentle Back of Beyond

It’s a landscape of gently rolling hills, covered in wheat and corn fields, or sunflowers bowing heavily with full heads. Rows and clumps of trees break up the fields here and there, together with streams and small ponds in clearings, where nothing stirs the surface of the water and the vegetation around is lush and fresh green even in the hight of summer. The smell of hay and manure wafts across the roads which lead to the villages. The roads are edged with rows of poplars and acacias, and in their shade in August you often see camping tables set out piled high with fresh watermelons for sale. A large number of the puszta hamlets had a name prefixed with mud (as in Sárszentlőrinc, Mud St Lawrence); not so surprising perhaps because the the nearby Sió (a river and canal in one which connects Lake Balaton to the River Danube) supplies abundant water in the area. There is even the odd castle or castle ruin: for example Simontornya castle (hardly more than a keep) still has cannon balls embedded in the walls; whether fired by the Turks or the Labanc (Austrians during the Rákóczi War of Independence) the locals no longer remember; it was just another siege they withstood.

Everybody knew everybody among the puszta folk in Illyés’s time, and that still applies a hundred years later. When I walk down the street in the village (there are hardly any pusztas that still exist), sooner or later I’m bound to be hailed “You, my child! Are you not the daughter of So-and-so?… How does it go with you?” And you find yourself answering deferentially to an old birdlike hag whose name you don’t know, and who is dressed in full black from the hand-embroidered kerchief tied around her head to the buttons on her sensible shoes. Because however far you have risen out of the puszta, you are still one of them. In the end, I’m only the second generation, the second person of the family to have let. I might not remember the old people are, but they sure remember me and this provides me with a strange reassurance that I, as an individual, matter.

Conclusion

All this and more Gyula Illyés writes about in his wonderful book. People of the puszta is a part an auto-biography, part sociography (of a society that has now mostly disappeared), part a description a landscape, meshed with bits of the cultural heritage of the people who inhabit that landscape. Overall, it’s a wonderful concoction of a book and I can only recommend it, even if you have zero interest in the topic as such. I leave you with this recommendation:

A beautifully written, moving work of art.

(The Times Literary Supplement)