Flight to Arras, or to give it its original title Pilote de guerre, ‘Pilot of War’, by Antoine de Saint-Exupery is set during the German invasion of France in 1940. In other words, it’s a war story. But if this makes you think you’re in for a cracking adventure, some kind of adult version of Biggles, think again. To take Flight to Arras for simply the story of a dangerous reconnaissance mission is falling wide of the mark. More than anything else, this book is a brilliant and moving description of the collapse of France fused with a philosophical discussion on the nature of war and defeat – told by a man in the cockpit of an aeroplane; a man who lived the story he’s recounting.

Glassfuls of Water into a Forest Fire

The plot of the book couldn’t be more straightforward: a reconnaissance aeroplane, with a crew of three men, pilot, observer and gunner, is sent to Arras to reconnoitre German positions:

“The major was sketching for us the afternoon’s program. He was sending us off to fly a photography sortie at thirty thousand feet and thereafter to do a reconnaissance job at two thousand feet above the German tank parks scattered over a considerable area round Arras.”

The pilot, Captain Saint-Exupéry and his observer, Lieutenant Dutertre are sitting in the major’s office, in a farm house. “Another crew flung away,” Saint-Exupéry says to himself, staring out of the window at the French countryside as he receives the orders given by the major in a voice “as deliberate as if he were saying, ‘and then you take the second street on the right to a square where you will see a tobacco shop’.” All three men in the room know that the sortie is “awkward”; and the major spent the morning arguing the order with the general, to no avail.

The chances of survival for the crew are not good. “Bad business,” the gloomy intelligence officer sums it up: “You’ll never make it.” Just what a man wants to hear before take-off. Not that Captain Saint-Exupéry has any illusions left by now. Even when a sortie is not “awkward”, only one out of three planes returns. In mere three weeks of fighting, their unit, Group II/33, has already lost seventeen planes out of the original twenty-three.

“Crew after crew was being offered up as a sacrifice. It was as if you dashed glassfuls of water into a forest fire in the hope of putting it out…”

What makes the situation worse is the futility of the exercise: the war has already been lost. It’s the end of May and the French army is in full retreat; the chaos among the troops on the ground and the high command is complete: the trouble with defeat is that there is no soldiering left for the soldiers to do.

You might think that in retreat and disaster there ought to be such a flood of pressing problems that one could hardly decide which to tackle first. The truth is that for a defeated army the problems themselves vanish. I mean by this that a defeated army no longer has a hand in the game. What is one to do with a plane, a tank, in short a queen of spades, that is not part of any known game? You hold the card back; you hesitate; you rack your brains to find use for it – and then you fling it down on the chance that it may take a trick.

Commonly, people believe that defeat is characterized by a general bustle and a feverish rush. Bustle and rush are the signs of victory, not of defeat. Victory is a thing of action. It is a house in the act of being built. Every participant in victory sweats and puffs, carrying the stones for the building of the house. But defeat is a thing of weariness, of incoherence, of boredom. And above all of futility.

Saint-Exupéry knows that even if he lives to bring the intelligence back, there’s no way to get it to the soldiers who could use it. He and his crew are going to dice with death for nothing.

“For in the first place these sorties on which we were sent off were futile. More murderous and more futile with every day that passed. Against the avalanche that was overwhelming them our generals could defend themselves only with what they had. They had to fling down their trumps; and Dutertre and I, as we sat listening to the major, were their trumps…”

…A last throw of the dice then, and the last card played.

A flight to Arras from which there is likely no return.

But I was not weighing my chances of getting back. Sitting there in the major’s office, death seemed to me neither august, nor majestic, nor heroic, nor poignant. Death seemed to me a mere sign of disorder. A consequence of disorder. The Group was to lose us more or less as baggage becomes lost in the hubbub of changing trains.”

War Is Like Typhus

I’ve read other books about war written by people who had fought. First-hand accounts of war in the air, on land and sea, or even under the sea. Some, like Winged Victory or The Cruel Sea were told in the form of novels, others, like Unbroken, the story of a British submarine on the Malta run in World War II, were straightforward autobiographical narratives. All were competently told and made good reads. Where Saint-Exupéry stands out is his ability to select and describe those crucial moments in the flow of events that characterise the whole. Flight to Arras picks out those telling moments in the chaos that is France during the collapse that show, to even the most unimaginative reader, what it must have been like to be caught up in the defeat.

We set up our haycocks against their tanks; and the haycocks turned out useless for defense. This day, as I fly to Arras, the annihilation has been consummated. There is no longer an army, there is no liaison, no materiel, and there are no reserves.

Nevertheless I carry on as solemnly as if this were war. I dive towards the German army at five hundred miles an hour. Why? I know! To frighten the Germans. To make them evacuate France. For since the intelligence I may bring back will be useless, this sortie can have no other purpose.

The collapse of France is shown through a string of small episodes: a lost platoon on a lorry trying to make their way back to the front against the tide of refugees coming the other way – until finally they are forced to give up and end lending a hand instead to the most needy civilians around them by giving them a ride on their lorry in the opposite direction. Bemused villagers watching the flood of displaced humanity roll through their village until a couple of weeks later the front reaches them and they too become part of it; the strained look on the pilot’s face who has just been ordered on a suicide mission; roads clogged by refugees with their carts piled high with bedclothes and cooking utensils weaving their way among broken down cars, fleeing “at the rate of two to ten miles a day… before tanks moving at fifty miles a day and aeroplanes flying at four hundred miles an hour”. And the rumours:

“…crazy rumors… sprouted by the roadside every mile or two in the form of ludicrous hypotheses… The United States had declared war. The Pope had committed suicide. Russian planes had set fire to Berlin. The Armistice had been signed three days ago. Hitler had landed in England.”

War the way Saint-Exupéry describes it has no glamour, and the courage of the men who fight it is not the showy kind. To wage war is not simply to accept risk, says Saint-Exupéry; it’s to accept death. War is a sickness:

“Elsewhere, I’ve experienced adventures: the creation of airmail routes, dissidence in the Sahara, South America… Adventure rests in the richness of the bonds it establishes, the problems it poses, the creations it inspires. It’s not enough to turn a game into adventure by imposing life and death stakes on it. War isn’t an adventure. It’s a sickness. Like typhus.”

A Carnival of Light

Flying at high altitude in 1940 is a cold business. As Saint-Exupéry and his crew don layer upon layer in preparation for the sortie, the pilot is vexed by little things. He can’t find his gloves. The chief-of-staff with his mania for low-altitude flying is an idiot. He can barely move in his bulky clothing. The intelligence officer, hovering like “a bird of ill omen”, offers information that he’d rather not hear. There’s certainly no thought of heroism in his head.

“There is no god here. There is no face to love. There is no France, no Europe, no civilisation. There are particles, detritus, nothing more. I feel no shame at this moment in praying for a miracle that should change the course of this afternoon. The miracle, for instance, of a speaking tube out of order. Speaking tubes are always going out of order…”

But he has no such luck. The intercom is in perfect working order, and whatever the intelligence officer’s assessment of the chances of survival, a captain can’t tell his general that he’d rather stay on solid ground.

The flight turns out to be quite as eventful as foreseen. Frozen controls, attacks by enemy fighters and finally, the anti-aircraft fire over Arras. As a writer, Saint-Exupéry always excelled at description; when he wrote, repeatedly, about the Sahara, he almost persuaded me that I like the desert (I cannot imagine anything more barren, brutal and boring than the desert). And he doesn’t disappoint in Flight to Arras: his description of the “carnival of light” caused by the anti-aircraft fire verges on the poetic.

Each burst of a machine gun or a rapid-fire cannon shot forth hundreds of these phosphorescent bullets that followed one another like the beads of a rosary… And I flew drowned in a crop of trajectories as golden as stalks of wheat. I flew at the centre of a thicket of lance strokes. I flew threatened by a vast and dizzying flutter of knitting needles. All the plain was now bound to me, woven and wound round me, a coruscating web of golden wire.

A Philosopher in the Pilot’s Seat

I’ve got this image of Saint-Exupéry in my head that originates in the figure of the pilot in The Little Prince which I read when I was ten; the image of a man in his thirties, perhaps, wearing the helmet and goggles and coat of the early pilots, those who flew in open cockpits.

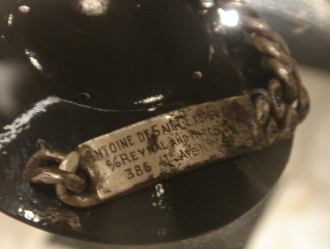

An image not unlike than this:

(Not that there was a drawing of the pilot in The Little Prince.)

The pilot of The Little Prince and the war pilot of Flight to Arras are of course the same person and thus share a love of philosophising. Saint-Exupéry was one of those writers unable to stop philosophising, moralising, even while he was telling a story. The Little Prince is a book meant for children yet teems with philosophical comments answering the great questions of life and love. In Wind, Sand and Stars, hallucinating with thirst after a crash in the Sahara, Saint-Exupéry was nevertheless still capable to consider the beauty of the desert and discuss the reasons that make men want to fly.

As he flies over defeated France, in Flight to Arras, Saint-Exupéry has plenty of time to think. While he watches 300 instruments and kicks the frozen rudders, he reflects on the meaning of war, the pointlessness of his orders, the confusion of high command. In between dodging enemy fighters and anti-aircraft fire he thinks about his impending death and the plight of the civilians trying to flee the war down below… Childhood memories pop up and snatches of conversations with fellow pilots, some of whom are already dead. He considers what civilisation is and questions himself why and what he is fighting for. What is the meaning of death, what’s the difference between defeat and victory?

“Where will I find that rush of love that will compensate my death? Men die for a home, not for walls and tables. Men die for a cathedral, not for stones. Men die for a people, not for a mob. Men die for love of Man provided that Man is the keystone in the arch of their community. Men die only for that by which they live.”

And yes, this philosophical wandering slows the book down; sometimes it goes on too long and gets in the way of the story. It even feels banal, pointless or irrelevant on occasion. And yet, this book is so rich in content, so rich in thoughts worth considering that when I started flipping through it intent on choosing a couple of quotes to accompany this post, I was faced with an overwhelming array of irresistible quotes. It’s only when you have finished the book, when you’re no longer in the cockpit with Saint-Exupéry – that’s when you finally are able to consider and appreciate some of the many ideas he threw at you during the flight.

“The course of a man’s destiny can seem sharply altered by a sudden illumination. But illumination is no more than the Spirit’s sudden vision of a road that is long prepared. Gradually I learned grammar. I practiced syntax. My feelings were awakened. Then a poem suddenly blazed in my heart.”

Missing in Action, Presumed Dead

Is Flight to Arras a faithful retelling of what happened? Did Saint-Exupéry fly this very mission to Arras? Or perhaps it is a fictional account built from the elements of various missions he flew. One thing is certain: Saint-Exupéry doesn’t lack authenticity as author. He wrote from experience. He flew reconnaissance planes during the war, flying missions like the one he described in the book. All of Saint-Exupéry’s books that I have read are based in his life and experiences.

“It was impossible for me not to contrast in my mind the two worlds of plane and earth. I had led Dutertre and my gunner this day beyond the bourne at which reasonable men would stop. We had seen France in flames. We had seen the sun shining on the sea. We had grown old in the upper altitudes. We had bent our glance upon a distant earth as over the cases of a museum. We had sported in the sunlight with the dust of enemy fighter planes. Thereafter we had dropped earthward again and flung ourselves into the holocaust. What we could offer up, we had sacrificed. And in that sacrifice we had learnt even more about ourselves than we should have done after ten years in a monastery. We had come forth again after ten years in a monastery.”

Saint-Exupéry didn’t stop fighting in 1940, after the defeat of France. He joined the Free French Air Force in North Africa, and disappeared in an unarmed P-38 over the Mediterranean Sea, off the coast of Marseille in July 1944 on a reconnaissance flight. His identity bracelet was found by a fisherman in 1998 and wreckage from his plane was discovered nearby two years later. To this day we don’t know the exact circumstances of his crash.

Each time, for a fraction of a second, it seemed to me that my plane had been blown to bits; but each time it responded anew to the controls…

There was just time enough for me to feel fear as no more than a physical stiffening induced by a loud crash, when instantly after each buffet a wave of relief went through me. I ought to have felt successively the shock, then the fear, then the relief; but there wasn’t time. What I felt was the shock, then instantly the relief. Shock, relief. Fear, the intermediate step, was missing. And during the second that followed the shock I did not live in the expectancy of death in the second to come, but in the conviction of resurrection born of the second just passed…

It was as if, with each second that passed, life was being granted me anew. As if with each second that passed my life became a thing more vivid to me. I was living. I was alive. I was still alive. I was the source of life itself. I was thrilled through with the intoxication of living.